| | | | | |

⌊⌊

1 Augustinus, in

[den|the]

Confession[en|s]

I/8:

[c|C]um

(majores homines) appellabant rem aliquam, et cum secundum eam

vocem corpus ad aliquid movebant, videbam, et tenebam hoc ab eis

vocari rem illam, quod sonabant, cum eam vellent ostendere.

Hoc autem eos velle ex motu corporis aperiebatur:

tamquam verbis naturalibus omnium gentium, quae fiunt vultu et nutu

oculorum, ceterorumque membrorum actu, et sonitu vocis indicante

affectionem animi in petendis, habendis, rejiciendis,

faciendisve

rebus. Ita verba in variis sententiis locis suis posita,

et crebro audita, quarum rerum signa essent, paulatim colligebam,

measque jam voluntates, edomito in eis signis ore, per haec

enuntiabam.⌋⌋ 1

In these words we

– it seems to

me – ⌊⌊In these words we are given, it seems to

me,⌋⌋ a definite picture of the nature of human

language. Namely this: the words of the

language objects – sentences are combinations of

such .

In this picture

of ˇhuman language we find the root of the

idea: every word has a meaning. This meaning is

correlated to the word. It is the

object which the word stands for.

Augustine

ˇhowever does not speak of a distinction between parts

of speech. Whoever Anyone who

ˇIf one describes the learning of language in this

way , one

thinks – I should imagine – primar [li|il]y of

substantives , like “table”,

“chair”, “bread” and the names of

persons; and of the other parts of speech as something that will

out all

right . eventually. | | |

| | | | | | Consider

ˇnow this application of language: I send someone

shopping. I give him a slip of paper, on which

I have written the

signs

are the marks |

: “five red apples”.

He takes it to the groce[s|r]; the grocer opens the

that

has the

“apples” on it; then he looks [y|u]p the

word “red” in a table, and finds opposite it a

co[ul|lo]ured square; he now

says out loud the series of cardinal

– I assume that he knows them by heart – up to

the word “five” and with each numeral he takes an

apple from the box that has the colour of the square

ˇfrom the draw. – In this way & in similar

ways one operates

This is

how one works |

with words. –

“But how does he know where and how he is to look up

the word ‘red’ and what he has to do with the

word ‘five’?” – Well, I

am assuming that he a[s|c]ts, as I

have described. The

[e|E]xplanations come to an end

somewhere. – ˇBut

[W|w]hat[i|']s the meaning of the word

“five”? – There was no

question of any ˇsuch an entity

‘meaning’ here; only of the way in

which “five” is used. // Nothing of that sort was being discussed,

only the way in which “five” is

used. | | |

| | | | | |

That philosophical concept of

meaning is at home in a primitive notion

of ˇway of describing

◇◇◇ ˇpicture of the

way in which our language functions. But

might

a[s|l]so say ˇthat it is the

notion ˇa picture of a more primitive

language than ours. | | |

| | | | | |

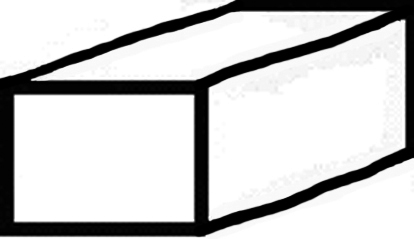

Let us

imagine a language for which the description which

Augustine has

given would be correct. The language

shall help is to be the means ˇof

communication between a bilder builder A

to make himself understood by an and his assistant B.

2 assistant

B. A is constructing a building out of building

; there

cubes,

columns, slabs and beams. B has to hand him the

buildingstones in the order in which

A needs them. For this purpose they use a

language consisting of the words:

“[C|c]ube”, “column”,

“slab”, “beam”. A

out the words;

– B brings the stone that he has learned to bring at this

call.

this as

a complete primitive language. | | |

| | | | | |

Augustine

describes, we might say, a system of communication;

only not everything,

ˇhowever, that we call

language is this system.

(And this

must be one must

sa[i|y]d in ever s[l|o]

many cases

whe[r|n]e

the question

arises, :

“can is this ˇan

appropriate description be used or can't it be

used? or ◇

not?”. The

answer is, “Yes, it is appropriate

can be

used |

; but only for this

narrowly restricted field, not for everything that you

were

profess[ing|ed] to describeˇ by

it.” Think of the theories of

the economists.) | | |

| | | | | | It is as though

someone explained: “Playing a game consists in

moving things ab[i|o]ut on a surface according to certain

rules …”, and we were to

answered him: You

thinking of games played on a board; but

th[o|e]se

aren't all games the games there are.

You can put your description right by confining it

explicit[yl|ly] to those games. | | |

| | | | | |

Imagine a

script in

[h|w]hich ˇ◇◇◇ letters

stand

for

are used to indicate |

sounds, but ˇare used also as accents

to

indicate emphasis |

and as

marks of punctuation

ˇsigns. (One can regard a

script as a

language for the description of sounds.) Now suppose

someone

script

a[d|s] though it were one in which to

every all letters there simply

corresponded a just stood for

sounds, and as though the letters ˇhere did not

have other very also have quite different

functions as well. – ˇSuch

[A|a]n oversimplified view of the

type our script like this one resembles

is the analogon, I believe,

ˇto

Augustine's

view of language. | | |

| | | | | |

If one

considers we look at our example (2)

one we may perhaps

get an idea

of

begin to suspect |

how far the concept of the meaning of

ˇa words surrounds the

of

language with a mist that makes clear 3 clear vision it

impossibleˇ to see clearly.

It scatters the The fog ˇis

dispersed if we study the

of

language in primitive kinds cases of

ˇits

application, in which it is easy

where the simplicity enables

one |

to get a clear

view of the ˇpurpose of way ˇthe

words function and of what their purpose

is. the way they function.

Primitive forms of language of this sort are what the child uses

when it learns to speak. And here teaching the language

does not consist in explaining but in training.

| | |

| | | | | |

We

imagine that the

language ([3|4]) is the

entire language of A and B; even the entire

language of a tribe. The children are brought up to carry

out just thesech

activitiesˇ in question, to use just

these such & such words and to

react in just this such & such

a way to the words of

anothers.

An important part of the training will consist in the

teacher's pointing to the objects, directing the

attention of the child's

attention to them and at the same time pronouncing a word; for

instanc[,|e], the word ‘slab’

in pointing to this block. (I

do_n[o|']t want to call this

“ostensive explanation” or

“definition”, because the child can't

ˇas yet ask what the thing is called.

I will call it “ostensive teaching of

words”. – I say

will constitute an important part of the training,

because

th[at|is]

is human beings, not because it

we couldn't be imagined

it

.) This ostensive teaching of

thech words, one might say,

an associative

connection between the word and the thing. But

what does that mean? Well, it may mean various

things; but probably what first comes to

one's mind is that occurs to one is

that an image of the thing comes

before the child's mind when it hears the

word. But suppose that happens – is that the

purpose 4 purpose

sig of the word? –

Yes,

[i|I]t may be

pu[s|r]pose aim. – I can imagine

ˇsuch a use of words

(i.e. here I mean

i.e. series of sounds).

having an application o[n|f] this

sort. (Their utterance is so

to speak the To pronounce them would be like

striking of a key on

piano of

.)

But in language

([[2|3]| 4]) it is not

the of the words

to call up

.

(Though it this may, of

course, turn out that this is conducive

be found to be helpful to their .)

But

if that is what the ostensive teaching brings about,

– shall I say that it brings about the understanding of the

word? Doesn't

understand the

“slab!” if he a[s|c]ts in

such and such a way on hearing it? – The

ostensive teaching ˇindeed helped to

ptoduced produce bring this no

doubt about, but only in

connection with a certain training

course of

instruction |

. With a

different training

course of

instruction |

the same ostensive

teaching of these words would have brought about quite a

different understanding. – Of

th[at|is]

more ˇat a later.

point.

[“|“]When I

By connecting ˇup

the rod with th[e|is] lever ˇwith

this rod by means of

peg, I

make put the brake ready for use

in order.” –

Yes, given all the rest of the mechanism. Only

together with this ˇmechanism is it a brake lever; and

withoutch detached from

its support it isn't even a lever, but it may be

anything

can be

all sorts of things, or nothing |

. | | |

| | | | | |

ˇIn the use of As the language

([3|4]) is used in

practice

the one party calls out the words and the other acts according to

them. But [i|I]n the

teaching instruction of th[e|is]

language ˇhowever you will find

there

will bech |

this

procedure: the calls the by ˇtheir

names; that

is, he

the word when the teacher points to the

. –

In fact will find

here an evench the

◇◇◇ simpler exercise: the pupil repeats

the words the

teacher recites to him ˇpronounces for

him: [B|b]oth

processes ˇof these

exercises already primitive uses of

that resemble

language. |

5 language.

We may even imagine that the entire process of the

use of the words ˇwe make in ([3|4]) is one of those

games by means of which ˇour children learn

our language. I will call these

“language games”, and ˇI will frequently

speak of a primitive language as a language game.

And one might call the

of

calling the

by their names and of repeating the words

that has been spoken out which the teacher has

pronounced language games as

well. Think of the various

the uses that are made of words

in nursery-rhymes. | | |

| | | | | | Let us

now consider an extension of the language

([3|4]): Besides the

four words “cube”, “column”

etc., let it contain a series of words

that are app which is applied in the

way in which the grocer in (2)

applie[s|d]

the numerals, – it

be the

sri series of the le

letters of the alphabet; further, ˇlet there be two

words, which we may

pronounce say let us

choose “there” and

“this”, since this ˇalready suggests

roughly their purpose, – they are

ˇto be used in connection with a pointing

gesture

movement of the

hand |

; and finally let us use

certain

of paper of various colours. A now

gives a command of sort:

“d slab there” – at the same

time letting the showing his

assistant see a coloured square, and

with the word “there” pointing to a

ˇcertain place. B takes from the supply

of slabs one a slab of the same colour

of as the coloured square for each letter of the

alphabet up to

“d” and brings it to the place

which A indicates. – On other occasions A

gives the command “this there” – with

“this” he points

a building

– and so

on. | | |

| | | | | |

When the child learns this

language it has to learn the series of

[“| “]numerals[”| ”]

“a”, “b”,

“c”, … by heart. – And it

has to learn their use. Will an ostensive teaching of

words into

this 6 this instruction

also? – Well,

someone

will point at slabs, for instance, and count: “a,

b, c slabs”. ˇThere would be

[A|a] greater similarity with

between the ◇◇◇ ostensive teaching in

example ([3|4]) would appear

in and the ostensive teaching of numerals

when if these are not used for

counting but refer

to

rather to indicate |

groups of objects that can be grasped

the eye.

ˇIn [T|t]his is

the

way children learn the use of the first five or six

cardinal

number[.|m]erals ˇDo we teach

Are “there” and

“this” taught ostensively? –

how might teach their

use. You point to places and things; –

but the

pointing occurs in the use of the words

,

and not simply in the

of

. –

| | |

| | | | | |

Now

[W|w]hat do the words of this language denote? – How can this show itself –

[w|W]hat they denote – except

ˇhow is this to appear, unless in the way they are used? And this

is what we have described. The expression, “this

word denotes that ˇso

& so” would have then to

be ˇnow become a part of this

description. Or: the description

be put in the

form: “The word … denotes

…”.

Now one can

it certainly ˇis possible to condense

shorten the description of the

use of the word “slab” into saying

in

this way, and say |

that

this word denotes this object.

Th[at|is]

is what one would do, for instance, if the

question was were simply ˇ, for

instance, to prevent the misunderstanding of

thinking that the word “slab” referred to

the kind of block

which

building stone that |

we actually call ˇa

“cube”, the ˇparticular sort of

“reference”,

i.e. all the rest of the game with

everything else about the

use of |

these

words,

familiar.

Similarly one might say that the signs

“a”, “b”,

“c”, etc. denote

numbers, when if this ˇis

to removes the misunderstanding

of thinking that “a”,

“b”[b|,]

“c”, play the role in

language which

actually is 7 is played by

“cube”, “column”,

“slab”. And one can say also that

“c” denotes this number and not that, –

when this is to explain, say, that the letters are to be used in

the order “a”, “b”,

“c”, “d”

etc., and not “a”,

“b”, “d”,

“c”.

But

because you by

assimilat[e|ing] in this way the

descriptionˇs

of the uses of these words to one

another, their uses

doesn't

more

similar[:| .] For, as we

have seen, their uses is

are of widely

different sorts. | | |

| | | | | |

Think of the tools in a tool

chest: a hammer,

a pair of pincers, a saw, a screw-driver, a ruler, a

pot of glue, glue, nails and screws. –

ˇAs [d|D]ifferent as the

functions of these objects are, just as

different are the functions of

words. (And there are similarities in the one case

and in the other.) | | |

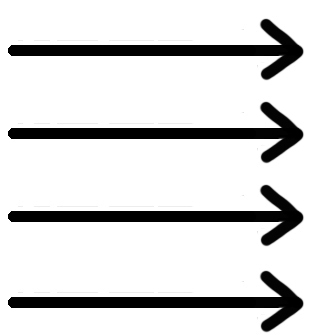

| | | | | |

What confuses us, of

course,ch is the uniformity of their appearance when

the we hear the words are spoken to us

or when we meet them in writing or see them

written

or in print. For their

isn't so clearly there

. Especially not

we are

doing

philosophy

philosophizing |

. | | |

| | | | | | It is

like As when we look

looking

into the driver's cabin of a locomotive: we see

handles all look

more or less alike.

(That's is

understandable natural, since

they are all

to be with

the ha[d|n]d.) ˇBut

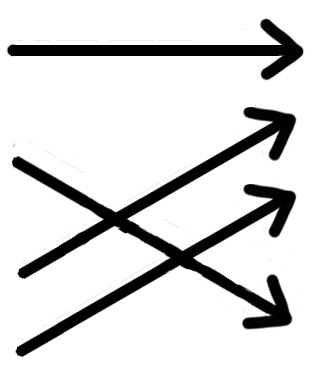

[O|o]ne is the crank valve

that can be moved ˇregulated by

continuously over degrees

(it regulates the opening of an air

valve); the

an other

is the handle of a switch, which has only two

ˇeffective positions, in which it

is effective it's either shut or

open; a third is the handle of a brake lever,

the

you pull it the more strongly the brake is applied; a

fourth, the handle of a pump, works only as long as it is

8 it is moved back

and forth. | | |

| | | | | |

If we say: “every word of

the language denotes something”, –

then, so far, ˇwe've

said nothing at allchch has

been said[;| ,] ˇthat is, unless we

explain precisely whatch distinction we

w[a|i]sh to make. (It might be that we

to

distinguish the words of ˇour language

() from

“nonsense”

“words ˇ‘without

meaning’ which such

as

oc[u|c]ur in Lewis

Caroll's

poems.) | | |

| | | | | |

Suppose someone

said, :

“All tools serve to modify something.

Thus the hammer modifies the position of the nail, the

saw the of the board,

etc..” – And

what is modified by the ruler, the glue pot, the

nails? // And

what's does

does

the ruler modify, or the glue pot, or the

nails? – “Our knowledge of the

length of

thing, the temperature of the glue and the firmness of the

.”

– Would anything be aained by this

assimilation under one of our

expressions? – | | |

| | | | | | The

word

“” ˇThe expression “the name of an

object” is very straightforwardly

probably

best |

applied where

the sign mark name is actually ˇa

mark on the object .

Suppose then that there are

scratched on the

tools which A uses in building.

A shows his assistant a

of this sort,

then the assistant brings the tool which bears that

sign. [(| // ]mark,

character // .

In this and

in more or less similar ways a name denotes a thing, and a

name is given to a thing. (Of this more

later.) – It will often proved useful

if we say to ourselves in doing

philosophy: Naming something, that

is something like attaching a lable

to

hanging a name plate

on |

a thing. – | | |

| | | | | | What about the

colour-samples that A shows to B, – do they

belong to the language? As you like. They

don't belong to language; but if I say to someone,

“Pronounce the word 9 the word

‘‘”,

you will count call the second

“the” also as part [f|o]f

the sentence. Yet it plays a very similar role to that of

a coloured in ˇthe language game

([9|11]): it is a sam[le|pl]e

of what the other person is supposed to say, just as the

coloured square is a sample of what B is supposed to

bring.

It is the most natural thing and

it causes the least confusion if we

the

samples among the instruments of the language.

| | |

| | | | | |

We may say that in language ([9|11]) we have

various parts of speech. For the functions of

“slab” and “cube” are more alike

than the functions of “slab” and

“d”. But

we

c[al|la]ssify the words together as various

parts of speech will depend on the purpose of the classification,

and on our inclination.

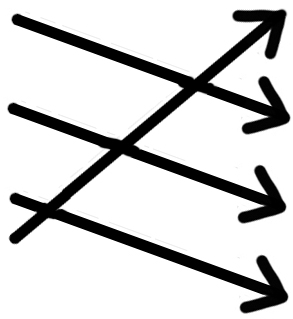

Think of the different

points of view which one mi[h|g]ht classify

tool[d|s] as different kinds of tools. Or chess

pieces as different kinds of pieces. | | |

| | | | | | Don't

let it bother you that the languages ([3|4])

and ([9|11]) consist only of

commands. If you are inclined to say that they are

theref[l|o]re incomplete, then ask yourself whether our

language is complete; whether it was complete before the symbolism

of chemistry and the infini[s|t]esimal calculus were

embodied in it: for these are, , suburbs of our

language. (And with how many houses or streets does a

begin to be a

?)

can

regard ou[t|r] language as an

onld

, a

quarter ˇthe center a maze of narrow

alleys and squares, old and new houses, & houses

with additions from various periods; and all this surrounded by a

mass of new suburbs with straight and regular streets and uniform

houses. 10 houses.

One can easily imagine a language which

consist[e|s]d

only of commands and

ˇreports

in battle. – Or a language which

consist[e|s]d only of questions and an

expression of affirmation and of

denial[.|–]

[A|a]nd countless othersˇ

things. – And to imagine a language means to imagine a way of

living. | | |

| | | | | |

But let's see: is the

“slab!” in example

([3|4]) a sentence or a word? – If it's a word, then

surely it hasn't anyway the same

meaning as the word “slab”

that's pronounced the

same |

in our

ordinary language, for in ˇour language

([3|4]) it is a

; but if

it's a sentence, then surely it isn't

the elliptical sentence “slab!” of

our language. ‒ ‒ ‒ As regards the first

question you can

call “slab!” a word, and you can

also call it a sentence; perhaps

a

“degenerate sentence” [,| (]as one

speaks of a degenerate hyperbola). And it is precisely

our “elliptical” sentence. ‒ ‒ ‒ But

that is surely just isn't this a

shortened form of the sentence, “Bring me

a slab”[,|?]

[a|A]nd there isn't any

s[c|u]ch a sentenc sentence in

([3|4]). – But

why should[I|n't] not

I rather call the sentence

“Bring me a slab” a lengthening of

the sentence “slab!”[,|?]

‒ ‒ ‒ Because the person who calls out

“slab!” really means “Bring me

a slab!”. ‒ ‒ ‒ But how do you do

th[at|is],

meaning this while you say

“slab”? Do you say the unshortened

sentence to yourself? And why should I, in order to

say what you mean by the “slab!”, translate

this expression into another? And if they mean the

same, – why shouldn't I say:

“When you say ‘slab!’ you mean

‘slab!’”? –

Or: Why shouldn't it be possible

for you to mean “slab!”, if you can mean

“Bring me the slab”? ‒ ‒ ‒

But when I shout “slab!”, then surely what

I want is 11 want is that he

bring me a

slab. ‒ ‒ ‒ Certainly, but does

“wanting this” consist in the fact that

youˇ, in some way, think in any

form a different sentence from the one you

speak? – | | |

| | | | | |

“Well

[b|B]ut if someone says ‘Bring

me a slab’ it looks

now as

though he could mean this expression as one long word, –

corresponding to the word one word

‘slab!’.” – Can one

mean it sometimes as one word and sometimes as four

words? And how does one generally mean it? – I

that what we

shall be inclined to say: is that we mean the sentence

as a sentence of four words when we are using it as

contrasted with sentences , “Hand me

a slab”, “Bring him a

slab”, “Bring two slabs”,

etc.: as contrasted, that is, with

sentences which contain the words of our command in

combinations. – But what does using one sentence

as in contrasted

with to other sentences consist

in? Does one have these ˇother sentences in

mind at the time? And all of them?

And while one is speaking the sentence, or before or

afterwards? – No. Even if such an

explanation has some attraction for us, we have only to

f[r|o]r a moment what actually happens in order to see

that we are on a

wrong track

the wrong road here |

. We say we use

th[at|is]

command as in

contrasted with

to other sentences because

our language contains the possibility of these other

sentences. // because in our language

these other sentences are possible. Someone who

did not understand our language, a foreigner who had

frequently heard someone giving the command “Bring

me the slab”, might suppose that this entire series of

sounds was one word and corresponded, say, to the word

“building

”

in his language. If he had then to give this command

himself, [w|h]e would perhaps pronounce it

differently and we 12 we should say:

He pronounces thi it so

because he

takes thinks it to be

is

one word. – But then doesn't

different

happen in him when he u[e|t]ters

, corresponding

to the fact that he takes views

regards the sentences to be

as one

word? The same thing may happen in him, or again

something different may. What happens in you

when you give a command of that sort? Are

you conscious that it consists of four words while you

are uttering it? Of course, you this language,

– in which there are those other sentences also,

– but is this

something

that happens while you are uttering the

sentence? – And I have admitted,

ˇthat the foreigner who views

the sentence differently will probably also pronounce it

differently,

will

probably give the sentence he views differently a

different pronounciation; |

but what we call

wrong

doesn't

in

anything that accompanies the uttering of the command.

(Of

th[at|is]

m[l|o]re later.) | | |

| | | | | | The sentence is

not ‘elliptical’ because it

something we

when we utter it,

but because it is

in as

compar[is|ed]onch with a

particular standard of our grammar. – One might

here make the obje[t|c]tion:

“You admit that the

and

the

sentence have the same meaning. –

Well,

[W|w]hat meaning have they

then? ?

Is Isn't there

not ex[r|p]ression for

this meaning?” – But doesn't

identical meaning

of the sentences consist in their having the same

?

(In Russian they say “stone

red” inste[da|ad] of “the stone is

red”; don't they get the full meaning, as

they leave out the copula

is the copula left out of the meaning

for them |

? or do they

think to themselvesˇ without

pronouncing it? –) | | |

| | | | | | One can

easily also imagine a language

also in which B, in reply to a

question by A, informs him of ˇhas

to report to him the number of slabs or

cubes 13 cubes

◇◇◇ ˇstacked up in some place; or

the colours of

building-stonesblocks. that lie in one

pla[v|c]e and

another.

The purport of such a report might then be:

“five slabs.”. Such a report might :

“five slabs.”. Now what is

the difference between the report, or

assertionch, “five slabs.”, and

the command “five slabs!”? – the role which these words plays in

language

games.

But ˇprobably the tone o[v|f]

vioce in which they are uttered will

probably be different , and the facial

expression and various other things. But it may well be

we

can also imagine |

that

the tone of voice is the same ˇin both cases – for a

command and a report

be uttered in different tones of voice and with

a lot of

different

various |

facial expressions – and that

the difference ˇmay lies

ˇonly in the application alone what is

done with the words “five

slabs”. – (Of course we might

also use the words “assertion” and

“command” ˇjust to indicate a grammatical

of a

sentence or and a

word ˇparticular

intonation, just as one ˇwould

calls

the sentence, “Isn't it glorious

weather today?”, a question,

even although it is used

like as an

assertion.) We could imagine a language in which

all assertions had the form and the intonation of a

rhetorical question; or ˇin which every command

ˇhad the form: “Would you like to

?”.

One

perhaps sayˇ in this case:

“What he says has the form of a question but

ˇit is really a command”,

i.e. has the function of a

command in the practical employment of

language. .

(Similarly one says “you will do

that ˇso &

so” not as a prophecy but as a

command. What ˇwould

makes it

the oneand , what the

other?) | | |

| | | | | |

Frege's view that in an assertion there

is contain[e|s]d

a supposal

Annahme,

and that it is this

is asserted, is

based really on the possibility that there is in our

language o[r|f] writing every 14 every assertion

sentence in the form: “It is asserted

that so and so is the case”. But “that

so and so is the case” is not a sentence in our language

–

is not ˇyet a move in our language game.

And if I write

insetad of “It is

asserted that …”, ˇI write “It is

asserted: so and so is the case”, then in this

case the words “It is asserted” are

quite superfluous.

We might very

well write every assertion in the form of a question followed

by an affirmative reply; thus instead of

“It's

is raining”, “Is it raining?

Yes.”. Would that show that

in eve[er|ry] assertion there

is contained a question? | | |

| | | | | | Of course one

has a right to use a mark of an asserion

ˇsign in contrast, for instance, to a question

mark. The mistake is only [in|to]

thinking that the assertion now consists

two acts, the

consider[ati|ing]in and the

asserti[on|ng] (assigning

the truth value, or whatever you call it

something of that

sort |

), and that we

perform these acts according to the signs

[in| of] the sentence,

as we sing

from notes. We might certainly

What can be compared ˇto

with the singing from notes is the reading

aloudly, or softly

silently, according to the

written to oneself, of the signs of the sentence

with singing from notes,; but not

“ˇthe meaning”

(ˇ◇the thinking) ˇof the

sentence that is read. | | |

| | | | | | The important

sense of point

about of

Frege's

mark of assertion ˇsign is put

perhaps ˇput best if we

by

say[:|in]g: it indicates clearly

the beginning of the sentence. –

Th[at|is]

is important:

our

phi[s|l]osophical difficulties concerning the nature of

[“| ‘]negation[”| ’]

and of

[“| ‘]thinking[”| ’],

originate spring in a sense,

from ˇare due

to the fact that we

don't

see ˇrealise that

an sentence

assertion “⊢

not p”, or

“⊢ I believe

p”, and the

“⊢

p” have

“p” in common, but not

“⊢

p”. (For if I hear someone

say, the words

“it's raining”, then I don't

know what he has said if I don't know 15 | | |

| | | | | |

know whether I I have heard the

beginning of the sentence.) | | |

| | | | | |

But [H|h]ow many

kinds of sentence are there,

though? ˇIs it

[A|a]ssertion[,|s],

questions and commands

perhaps? – There are

innumerable kinds: innumerable different

kinds of use

applications

of that we

call “signs”, “words”,

“sentences”. And this variety is

nothing ˇthat is fixed, given once and for

all, but new types of language, new language games

– as we may say – and others

obsolete and

are forgotten. (We can get

[a|A] rough picture of this ˇwe

ˇcan get if we look at

from the

in which happen in

mathematicsˇ seeing.)

The expression “language

game” is supposed used

here to emphasise here that the

speaking of the [,|l]anguage is part of an activity,

of a way of

living. of human

beings.

Bring the

ˇTo get an idea of the enormous variety of

the language games before your mind by

consider

these these and other

examp[,|l]es,ˇ &

others:

giving [C|c]ommandsch

commanding, and acting according to commands;

giving a

describ[ing|tion]

ˇof an object acco[dr|rd]ing to its

appearance by describing what it look like, or

according to by giving

it's

measurements;

producing an object according to a description

(drawing);

reporting an

course of events;

a hypothesis and testing it;

present[ati|ing]on

of

the results of an experiment in tables and diagrams;

acting a

play

performing in a theatre |

;

singing a catch;

guessing asking riddles;

& guessing them;

16 riddles;

making a joke, or telling one;

solving

an example

problem in

applied arithmetic;

translating from one language into

another;

,

thanking, swearing, greeting, praying.

– It is interesting to

compare the variety of the instruments of our language

and of their applicat

ways they are applied their various

uses – the variety of the parts of

speech and of the kinds of ˇwords &

of sentences – with

what logicians have said about the structure of ˇour

language. (And ˇIncluding

the author of the

Tract.atus

Log.ico-phil.osophicus

as well.)

| | |

| | | | | |

If we don't see that there is a multitude of

language games, we are inclined to ask: “What

is a question?” Is it the statement that I

don't know so and so, or ˇis it the statement

that I wish the other person would tell me …?

Or is it the description [f|o]f my mental state of

uncertainty? – And is the cry

“help!” ˇsuch a

description? of that

sort?

Think of what widely

different things we call

“description[”|s]”:

the description of the position of a body by means of its

coordinates: the description of a sensation of pain.

One can [O|o]f course

put instead of one can replace the usual form of

the a question

ˇby that of

statement or

ˇa description: ˇsuch as “I want

to know whether …”, or “I am in

doubt as to [h|w]hether …”

– but one hasn't thereby brought the different

language games any nearer to one another.

The

s[u|i]gnificance of such this

possibilit[i|y]es of transforming,

for instance, all assertions

declarative

sentences |

into sentences that

begin 17 begin with the

“I

think” or “I believe”

(i.e. so to speak into descriptions of my

)

will appear later. | | |

| | | | | |

It is sometimes

said: animals don't speak, because

they

the

ˇnecessary intellectual capacities. And this

means: ‘they don't think, therefore they

don't speak’. But the fact is

that they just don't speak.

Or : they don't use

language. (If we

disregard except

the most primitive forms of language.)

, askingˇ questions,

,

prattling, belong to our natural history just as walking,

eating, drinking, playing do. (It makes no difference

here whether the speaking is ˇdone with the

mouth or ˇdone with the hand.)

| | |

| | | | | |

This is connected with the view fact that

ˇwe think that the the learning of

the language consists in naming objects;

human beings,

, colours,

, moods,

numbers, etc..– As we

have said, – naming is something like

affixing a nameplate

to

a label to a thing. ˇAnd

this [O|o]ne may might

call this

the a preparation for the use of a

word. But for what is it a

preparation? | | |

| | | | | |

“We name things and can now

ˇwe can

talk about them[.|;]

We can refer to them in what we

say.” – As though with the act

of nam[k|i]ng we had ˇall

that happens after it were already at hand

fixed what we go on to do

afterwards. As though there were only one thing

that is called “speaking about

things”. Whereas actually

we do

things of the most widely different kinds

ˇof things with

our sentences. Think only of the

int[r|e]rjections. –

[W|w]ith their

entirely utterly very

different functions.

Water!

Away! // Get

out!

[I|O]uch!

Help! 18 Help!

Beautiful! // Lovely!

No!

Are you still inclined to

call these words “giving

“names

[to|of]

objects”? | | |

| | | | | | In

t[e|h]e languages ([3|4]) and

([9|11]) there was no such thing as asking

what

someathing is called. This and its correlate, the

ostensive explanation, definition, is, we might say, a separate

language game. That means really: we are

, trained,

to asked “What is

th[at|is]

called?”, – and then the

nam[i|e]ng follows

is given. ˇAnd

[T|t]here is also a language gameof : inventing a name for

something. I.e., to

say

That is, of

saying |

, “Th[at's|is

is] called …” and then

the new

name. (In this way, ,

children name their dolls and [g|t]hen go on to talk

about them. In this connection consider at

the same time how what a

ˇvery special use ˇwe

make of a personal name: it is

when we use it to call someone.) // … how speci[l|a]l that

use of a personal name is with which we call the person

named.) //

Now

you we can give an

ostensiv[e|ly]

defin[i|e]nition a

personal name, a colour word, [a| the] name of a

material, a numeral, the name of a direction

// the name [f|o]f a point of the

compass // , etc.,

etc.. The defin[t|i]tion of

two:

“Th[at|is]

is called ‘two’” –

pointin[t|g] to two nuts – is perfectly exact. – But how can you define

“two” in

th[at|is]

way? The person to whom you are

giv[i|e]ng the definition

know then what ˇit is you

w[ant|ish]

to call “two”; he'll suppose that you

are have

call[in|ed]g this group of nuts

“two”. – He may suppose

this, – but perhaps he won't

suppose it. . He

might also do just the opposite: when I want to assign a name

to this group of nuts he might take this

the name

19 name of a

number. And equally, if I give an ostensive definition

of a personal name, he might take

to be the name of a

colour, the name of a race, even the name of a

direction ˇpoint of the

compass. That is, the ostensive

de[r|f]inition can in every

cases be interpreted in one this

way or and also in others. in that

way. | | |

| | | | | | You may

say: “Two” can

be defin[t|e]d ostensively only in thisch

way: “This number is called

‘two’”[,|.]

[f|F]or the word “number”

shows here in what place in

the our language – in the

our grammar – we set ˇput

assign to the

word; but this means that the word “number” must

be explained before that ostensive definition can be

understood. – The word “number” in

the definition does

indicate

this place, – the post to which we

assign ˇto the word. And we can prevent

misunderstandings in this way, by saying,

“This colour is called so and so”,

“This length is called so and

so”, etc.. That

is: misunderstandings are often avoided in this

way. But can the word “colour”,

then, or “length”, be

understood [i|o]nly in this way? –

Well, we'll

ˇshall have to explain them. ˇThat

is[–|,] [E|e]xplain them

by ˇmeans of other words, that

is! And what about the last explanation

in this chain? (Don't say:

“There isn't any ‘last’

explanation”;.

[t|T]h[at|is] is exactly as though you

were to sa[y|id], “There

isn't any last house in this street: you can

always build ˇanother one

further”.) .”)

Whether the word “number”

ˇis necessary in the ostensive definition of

“two” is

necessary depends

on ˇupon whether he

understands this word differently

takes this word in a different sense

from the way I wish him to the one I

wish ˇmisunderstands my definition if I

leave out the word. And

th[at|is]

will depend on the circumstances under which I give it

the definition is given and on the person to whom I give

it. 20 give it.

And how he “understands” the explanation

ˇwill appears in how

the way he makes use of th[w|e] word

explained. | | |

| | | | | |

One might say then:

The ostensive definition explains the use – the

meaning – of the word if it is already clear in

general what ˇkind of role the word is to play in

the language. Thus if I know that someone wants to

explain a colour word to me, then the explanation

“Th[at'|is

i]s called ‘sepia’” will

help make me to get an

understanding of the

word. – And you can say this as long as you

remember

if you

don't forget |

that there are all sorts of

questions connected with now attach

to the

words

“ˇto know”

“be

clear”.

You have to know something

already before you can ◇

in order to be able

to |

ask what it ˇsomething is

called. But what do you have to know?

If you show someone the king in a ˇset of chess

game ˇmen and say,

“Th[at|is]

is the king of chess”, you do not thereby explain to him the

use of this piece, – unless he already knows the rules of the

game except for this last point: the

of the

king-piece..

We can imagine that he has learned the rules of the game without

ever having been shown a real chessman. The

of

chessman corresponds

here to the sound or the shape of a word.

But we

can also imagine someone's having lea[v|r]ned the game

without ever having learned or

formulated [v|r]ules. He has perhaps first learned very simple games on

boards by watching them and has proceeded to more and more complicated

ones. To him also you might give the

explanation,

“Th[at|is]

is the king”, if, for instance, you are showing him chess

of an unusual

. And

this explanation teaches him the use of the

only because, as we

21 we

might say, we had in the game already prepared the

place in which it was

the place in which it was put was already

prepared. |

Or again: We shall say the explanation

teaches him the use, only when the pla[v|c]e

is has already

ˇbeen prepared. And it is so

here ˇprepared in this case not

because the per[os|so]n to whom we are giving the

explanation already knows rules, but because he [a|h]as

ˇin a different sense, already mastered the

a game. in a different

sense.

Consider still another

case: I explain the game of chess to someone and begin by

showing him a pieceand ,

saying,

“Th[at|is]

is the king”. –

[He| It] can move in this and this way,

etc. etc.”. –

In this case we shall say: the words

“Th[at|is]

is the king” (or,

“Th[at|is]

is called ‘king’”) explain the use

are an

explanation |

of

the words ˇ“the

king”, only if the person

already

“knows what a piece in a game

is”: when he has already played other

games, say, or “has watched

the play ‘with

unders[a|t]anding[”|’]

ˇgames played by other people, and . And only

then will he be to ask relevantly, in learning the

game, “What's

th[at|is]

called?” –

, this

piece.

We may say: it is

sensible for there is only sense in

someone's to

asking what ˇfor the

name is only if he

knows already what to dow with

it. the name.

For

[W|w]e can imagine also that the person

who is we I have

asked, answers, “decide on

the give it the a name yourself”,

– and then the person whoˇever asked the

question I whshould have to

make himself responsible for everything catch on to

provide everything

himmyself. | | |

| | | | | | Anyone who comes

into a foreign

will often

have

has frequently |

to learn the language [f|o]f the

inhabitants there

ostensive

which

give him; and he

will often

have

has frequently |

to guess the interpretation of these

explanations, ˇ& will guess it

correctly,

wrong[.|ly.]

And now we can

say, I think: 22 And now we can say, I

think: Augustine describes learning of

h[i|u]man of language to

speak as though the child

to a foreign

country and did not without

understanding

language; that is, as though the child already had a

language, only not this one. Or, as though the child

could already think but could not

speak yet. And here “think”

ˇwould

means

something like: speak to

onehimself.

| | |

| | | | | |

But what if someone

objected, :

“It

is_n[o|']t true that someone

you must ˇalready have mastered a

language game already in order to understand

an ostensive definition, butch

only he's has

only – obviously – ˇof course, you've

got to know (or

guess) what the person

explaining ˇman who gives the explanation

is pointing to[.|:]

ˇe.g.,

[W|w]hether, for

instance, to the

of

object, or to its

co[,|l]our, or to the number ˇof ˇthe

objects, [t|e]tc.,

etc..” – And what does

“pointing to the

”,

“pointing to the colour” etc.

consist in, then? Point to a piece of

paper. – And now point to its

, –

now to its colour, – now to its number

(that sounds queer). – Well, how did you do

it? – You will say you

“meant” something different each time you

pointed. And if I ask

you how that takes place this is

done ˇyou do this, you will say you

directed concentrated

your attention on the colour, on the

etc.. But

I ask again how

th[at|is]

Suppose someone points to a vase

and says, “Look at

th[at|is]

marvelous

blue! – the shape doesn't matter.”

– Or, “Look at

th[e|is]

shape! – the

colour''

is unimportant.”

– Undoubtedly y[p|o]u will do

ˇsomething different things

in each case if

you do

what he asks you

comply with both these requests |

. But do you always do the

same ˇthing when you direct your

attention to the colour? Imagine various

cases – e.g.

these: –

I will suggest

some: |

“Is this blue the same as that? Do

you see a 23 see a

difference?” –

You are mixing

paints on a palette

colours |

and you say, “This blue of the

sky is hard to .”

“It[s|']s going to be

fine, you can see the blue sky already

again.”

“Look what

different effects these two blues give.”

“Do you see

th[e|at]

blue book over there? Please

it.”

“This blue

signal light means …”

“What'[i|s]s this blue called?

– is it “indigo”–?”

Directing the attention to the

colour sometimes means shutting out the outlines of

shape with

hand, or, not ˇlooking

direct[in|ly]g one's

gaze at the contour of the thing; sometimes ˇit

means starring at the thing and trying to

remember where one has seen this colour before. You

direct your attention to the ˇshape of a thing,

sometimes by

it,

sometimes by half closing the

eyes

squinting |

ˇscrewing up the eyes so as

not to see the colour clearly, etc.,

etc.. I

to sayˇ

that: this and things like it is the

sort of thing that happens

while one you

[“|‘]directs the

one's your attention to .

But th[at|is] is not the only

thing that allows it isn't just this which

makes us to say, ˇ that someone is directing his attention to the

shape, to the colour, etc..

Juts as

“making a move in chess”

does_n[o|']t ˇonly consist in

the fact that pushing a piece is

from pushed accross the board in such

and such a way here to there –

in the

thoughts and feelings that accompany the move in the person

making it – but rather in the circumstances that we call

“ a ”, or

“solving a chess problem”, and

.

| | |

| | | | | |

But suppose someone

sa[ys|id], :

“I always do the same thing when I direct my attention to

shape: I

[h|f]ollow the

with my

24 my eyes

and with the

feeling

[ …| …]”. And suppose

this person gives to someone else the ostensive

,

“Th[at|is]

is called ˇa

‘circle’”, by pointing,

with all these experiences, to a circular object

ˇ& having all these experiences[:|.]

–

[c|C]an't the

other person still interpret this explanation

differently, even

although he sees that the person giving

follows

the shape with his eyesand , even

he feels what the

person giving the explanation feels? That

, this

“interp[e|r]etation” consist in the way

in use which he makes now

uses makes of the word,

what he in his

point[s|i]ng to when he is

ˇsuch & such an object when given the

command, :

“Point to a circle”. – For

neither the expression, “meaning the explanation in such and

such a way”, nor the expression, “interpreting

the explanation in such and such a way”, indicates a

process

which

accompan[ies|ying] the giving and

of the

explanation. | | |

| | | | | |

There are

what

one can we may ˇmight

be called

“characteristic experiences”

ofor

pointing ˇ(e.g.) to

the a shape , e.g.

(for instance).

For

example instance,

[t|T]racing

the contour outline with one's

fingerˇ, for instance, or with

one's

, in

pointing. – But just as little

as just as thisch

ˇdoesn't happens in all cases in

which I [“|‘]mean the

shape[”|’], –

equally – similarly little is it true that there

isn't any no other

characteristic process ˇeither

occur[[s|ing]|s] in all these

cases. But

if

something of the sort such

process did

[re|oc]cur

in all of them, it would still de[e|p]end

the

circumstances – i.e.

upon what

happened befo[e|r]e and after the pointing –

whether we

L[sh|w]ould

say, :

“He pointed to the shape and n[t|o]t to

the colour”.

For the

“pointing to the shape”, “meaning the

shape” etc. are not used

like these as

are like these:–

“pointing to the book”,

“pointing to the letter

‘B’ and not to the letter

‘u’” etc..

– For Just think only

of how differently we learn the use of the

:

“pointing to 25 | | |

| | | | | |

to this thing”, “pointing to that

thing”, and on the other hand “pointing to the

colour and not to the shape”, “meaning the

colour”, etc.,

etc..

As I

say ˇAs I have said, in certain

cases, particularly in pointing

[“|‘]to the

shape[”|’], or

[“|‘]to the

number[”|’], there are characteristic

exp[r|e]riences and ways of pointing,

– “characteristic” because they

frequently, (not

[wa|al]ways[,|)]

[re|oc]cur

where shape or number is

“meant”. But do you

also know a characteristic experience for pointing to a

figure piece in a game chessman

as piece in a game a

chessman? – And yet may

say, : “I

mean this chessman

piece in the

game |

is called

‘king’, not this particular

[f|o]f wood that I'm pointing

to.”

And we do

here, what we do in

similar

cases:

we

mention ˇpoint out

some one bodily action

we call

“pointing to the shape”

(as opposed, e.g., to

the colour) we say ˇthat a mental activity

corresponds to these words.

Where our language

leads us to expect a body ˇlook for a

physical thing, and there isn't

any

we are inclined to

say, is a mind. put a

spirit. | | |

| | | | | |

“What is the relation between

names and ?” [)| –]

Well, what is it? Look at

ˇthe our

lang[au|ua]ge game ([3|4]), or

ˇat some otherˇ language game; you

can that's where you'll see

there what this relation consists

in. This this relation

may, [a|A]mong various

other things, consist also in the fact that

hearing the name calls up an image of the thing

named in our minds,, and it

ˇsometimes consists among other things also in

the fact that the name is written on the thing named, or that

is

it uttered when the thing named is

pointed t[l|o].

But what

does is the word “this”

ˇa name ˇof in ˇthe

language game (9), or 26 or the word

“that” in the ostensive explanation

“th[at|is] is called …”?

Well, if you don't want to

ˇproduce confusion it is best

not to say that these words name anything.

– And, curiously

enough, it was once said of the word

“this” that it is the real name.

Ever[e|y]thing else that we call

“name” is so ˇbeing a

name only in an inexact, appro[c|x]imate

sense.

This curious view has its origin in a

tendency to sublimate – as we might call it – the logic

of our language. The proper

answer to it is:

[W|w]e

call widely different things “names”; the

word “name” character[s|i]ses many

different

sort[f|s]s kinds of

uses of a

word[,|s], related to one

another each in many different ways; – but

among these kinds of

uses is

not that of the word “this”.

It is true that we often, in

ˇgiving an ostensi[c|v]e

defi[t|n]i[o|t]ion, point to

thing named

and in doing so pronounce

name. And similarly we pronounce in an

ostensive definition the word “this”

as we in

pointing to

thing. And the word “this” and a name

ˇcan often stand in the same

context

have the same

syntax |

: we say “Fetch

this”, and also “Fetch

Paul”. – But it is

precisely one of the characteristic features of a name that

is explained by

t[e|h]e demonstrative

“Th[at|is]

is N” (or

“Th[at|is]

is called

‘N’”).

But do we also explain,

“Th[at|is] is called

‘this’”[,|?] or

perhaps even “This is called

‘this’”?

| | |

| | | | | |

This is connected with the

of naming

as, so to speak, an occult processˇ, as it

were.

The

[n|N]aming appears as seems

seems to us like ˇto

be a strange

connection of between a word with

the and an object. – 27 a word

object.

– And

strange connection does really take place

is made

namely when the philosopher, in order to what thech

connection is between a name and

thing named,

stares an an object before

him, and at the same time

repeat[s|ing] a name – or it

maye be the word “this” –

over and over again. For thech

philosophical problems arise when language

id[e|l]es. And then

ˇindeed we may its easy to

even imagine well

enough that naming

is some

mental act, as it were a kind of christeningˇ,

as it were, of

the object. And similarly we may

then also say the w[r|o]rd “this”

as it were to the object,

addressˇing

it

a/strange use of

this word, that probably

occurs which, I thinkm is never is

made only when we are outside doing

engaged in

[P|p]hilosoph[[y|i]|y][.

–|sing].

– | | |

| | | | | | But what gives people the idea of wanting to make why

should one wish to regard just this word

ˇas a name, when it so obviously isn't a

name? –

For this very

reason

Just that |

; for

th[y|e]y we are

inclined to make an raise an

objectionion to

ˇcalling “ˇa name” what is

generally called “name”

so; and

th[e|is]

objection can be expressed by

saying

put in this way |

: that the name really ought to

something

simple.

And for this one can might

give say the following reasons be defended as

follows:–

A proper name in the ordinary sense , ,

the word

“Noth[i|u]ng ˇEscaliber”.

The sword Nothung

consistsed

of ˇvarious parts put together in a

way.

If they are not put together differently

in a different this way then Nothung

doesn't exist.

Now the sentence “Nothung has a sharp

edge” obviously has

,

whether Nothung is still whole or has been smashed to

bits.

Yet if “Nothung” is the name of an

object, then this object doesn't exist any more when

Nothung has been smashed; and since the name

wouldn't then

ha[v|s]e any no object

corresponding to it then, it wouldn't have

hasn't any

meaning.

But then in the sentence, “Nothung has a

sha[p|r]p edge”, there a word meaning, and

so ˇtherefore “Nothung has a sharp

edge”

the

sentence |

would be

28

would be nonsense.

But ˇto say th[e|is]

sentence

does have meaning, and so ˇto the words of

which it consists must alwaysch correspond

to something.

in

analysis of the

meaning ˇsense

◇◇◇ the word “Nothung”

must disappear, and instead of it

in its

place |

must come

words ˇmust appear that name which

stand for ˇdenote

something simpleˇ

objects.

And [t|T]hese words we may reasonably call

the real names. | | |

| | | | | | Let us ˇfirst of all discuss one this

point of this the argument first of

all:

namely that the word has no meaning when nothing corresponds to

it. –

It is important to

that the word “meaning” is used ungrammatically

if one when use[s|d]

it to

indicate the thing which

[“|‘]corresponds[”|’]

to the wordˇ ‘stands

for’.

This confusing the

meaning of the name with the bearer of the name.

If Paul then we say the bearer of the name is dead,

but the meaning of the name is dead.

And it would be

nonsensicaleical

to speak that way say such a

thing ˇthis, for if the name

ˇhad ceased to have meaning, then it

wou[,|l]d have no meaning to say,

“Paul ”. | | |

| | | | | | In (1[3|9]) we introduced proper names into

ˇour language ([9|11]).

Now suppose the tool with the name (α)

is were had

been bro[p|k]en.

A doesn't know this, and gives B the

sign (α): has this sign ˇa meaning

now, or ?

–

What'sis B supposed to do when he

receives this sign? –

We have made no agreement about this.

You might ask, what will he do?

Well, perhaps he will stand there perplexed, or show A the

pieces.

You might say

here, :

(α) has become meaningl[l|e]ss; and this

expression would indicate that there is now no further use for the sign

(α) in o[r|u]r language game

(unless we (were

to) give it a new one).

(α)

also become meaningless

we, for any

some reason whatever or other,

ˇwe scratched a different

mark sign mark on the tool and

didn't no longer use the sign

(α) in the game any

more. –

But we can also imagine

29 imagine an agreement

accord[n|i]ng to which, when a tool is broken and A

gives ˇshows B the sign of

this tool, B has to shake his head as an answer to

him. –

This gives, we might say,

ˇgives the command (α) a place in the

language game, even

tool no longer

exists.

And we can now ˇwe may say that the sign

(α) has a meaning even when its bearer

has

cease[s|d] to exist. | | |

| | | | | | We may

[f|F]or We may –

for a large class of cases in which the word

“meaning” is used– , though not for all

cases of its use, – explain this word

thus:

Tthe

meaning of a word is its use in the language.

And we explain

the meaning of a name by pointing to the

it's bearer.

of it. | | |

| | | | | | “But, in that game, do

names ˇsigns that

ˇhave meaning also which have never been used

for a tool have meaning as well too?”

Let's suppose that “X” is such a

sign

and A

to B.

– Well, [s|S]uch a

signs – Signs of this sort

might may ˇalso be included

embodied in the our language game, and B

might be supposed, expected

say, to answer it them also by shaking his

head.

One

ˇe.g. imagine this

as ˇto be a way

the two of them had of [i|a]musing

themselves. of making their work more

pleasant. | | |

| | | | | | We said that the sentence, “Nothung has a

sharp edge”, has

even

Nothung has

already been broken to pieces.

Now

th[at|is]

is so because in this language game a name is also used

in the absence of its bearer.

Butw we can imagine a language game with names

( [i|w]ith signs

we should

certainly also call

“names”) in which names are

used only in the presence of their bearers.

Suppose, say, [f|t]hat we were watching a surface

on which coloured spots were

are

mov[i|e]ng ˇabout (as on the screen

a cinema).

There are three such spots, which slowly change their shapes

and positions.

Suppose I

ha[d|ve]

named them “P”,

“Q” and “R” by giving

os[e|t]ensive definitions.

Our 30 Our language

describes the changes of these three, and sentences

like, : “Do

you see how P is contracting now and is approaching

R?”. –

Now in this language

names are supposed to be used as synonyms

for the demonstrative pronoun “this”

together with (the

plus pointing to a coloured

spot).

ˇThus

[i|I]f one of the three spots disappears, then I

may can't say “P has

disappeared” – any more than I should say “this

has disappeared” – but we ˇmight say

rather,

“[T|t]he

letter ‘[p|P]’ drops

is out of use”.

In this language

say, a

name loses its meaning its bearer

ceases to exist, and the ˇthere is something

words signs words ˇwhich corresponds to

the words “P”, “Q” and

“R” always have something corresponding to

them as long as they have any meaning

– use in the/language game – at all.

(For in the sentence,

“‘P’ drops is

out⌊”⌋ of use, the sign

““‘P’””

occurs, but not “P”; and I assume that we

do'_n[o|']t speak about past

,

another some mode of expression .)

In this language game, then, a name

canno't

cease to have a bearer; only this isn't any

advantage asset of the language game[,| ;] for

even when it hasn't a bearer a name may

can have a purpose, use, i.e.

meaningˇ without having a bearer.

(ˇAnd

[T|t]hus,

ˇe.g., the name

“Odysseus” has

meaning.) for

instance.) | | |

| | | | | | But language game can,

I think, show us a reason why one to make

ˇsay that the demonstrative pronoun

ˇis a name: for the

demonstrative “this” can never be without

a meaning bearer.

One might say, :

“So long as there is a this, then the

word [‘|‘]this’ has meaning, no

matter whether this is simple o[f|r]

complex.” –

But does

not make it a name.

On the contrary, – for we don't

use a name by making isn't used with a

deomnstrative gesture, but only

explained it by it. | | |

| | | | | | What is the position with regard to whether names really

Now what about this matter of names

31 really

standing for simple? –

Socrates (in the

Theaetetus): 32

These primary elements were are

a[sl|ls]o what

Russell's

“individuals” were, and my

“objects” (Tractatus

Logico-philosophicus). | | |

| | | | | | But what are the simple

[f|o]f

which reality is ? –

What are the simple

of a

chair? –

The pieces of wood out [f|o]f which it is put

together?

Or the molecules?

[o|O]r the electrons?

“Simple” means: not

.

And

th[en|us]

it all depends on: in what sense

“”?

It makes no sense

is senseless |

to talk about the “simple components of a chair”

without qualification.

Or: Does my visual

the

visual appearance I get of th[ei|is] tree, or

of this chair, consist of parts?

[a|A]nd

what are its simple components?

Being of different colours is kind of

complexity; another is, , the

composition of this broken

out of straight

bits.

A[d|n]d you

call this a say that this curve out of straight

bits.

A[d|n]d you

call this a say that this curve

a complex

compound of was made up of an

ascending and a descending

. a complex

compound of was made up of an

ascending and a descending

.

If I say to someone without further

explanation, :

“What I now see before me is complex”,

then he will be quite correct in

rightly asking,

you: “What

do◇ you mean by ‘complex’?

Th[at|is]

mean all sorts of

things.” –

The question, “Is what you see

complex?”, does have meaning if it is already clear what

sort of complexity – i.e., what

particular kind of use [f|o]f this word –

is supposed to be in question we

are referring to is in question.

If it ha[s|d] been

,

, that the

visual

of

a tree be called

complex if you see not only a trunk but also branches, then the

question, “Is the visual appearance of this tree

simple or complex?”, and the

question, “What are its simple

components?”, would have a clear

use ˇsense, a clear use.

And the answer to the second questionˇ is, of course,

is

not,:

“[T|t]he

branches” (this would be an answer to the

grammatical question “What

d[l|o]es one call do you

call here ‘simple components’

here?”) but

rather a description of the individual

branches. | | |

| | | | | |

33

But isn'tˇ, say, a chess board, for

instance, obviously and w[k|i]thout qualification

complex? –

I suppose

you're

You are probably |

thinking of its being of 32 wh[a|i]te and 32

black squares; :

– but mightn't you sayfor

instance also , e.g.,

that it is made up of the colours [b|w]hite, black and the

pattern of net of

squares?

And ˇso, if there are entirely different ways of

looking at it, do you still want to say that the chess board is

[“|‘]complex[”|’]

without qualification?

The mistake of asking, outside ˇof a particular

game, : “Is

this object complex?”, is similar to that which a small

boy once made who had whether the verbs in this

and that such & such sentences

was were used in the

active or ˇin the passive form, and who

then pondered the

question

reflected |

ˇnow tried to puzzle out whether

for instance the verb “to sleep”ˇ,

for instance, meant something active or something

passive.

The word “complex” (and so the word

“simple”ˇ also) is one that

we used ˇby us in innumerable different ways, connected in

various ways with one another

each.

(Is the colour of this square

the chess board simple,

or does it consist of pure white and pure yellow?

And is the white simple, or is it of the colours of the

rain_bow? –

Is this of

2 cm simple, or does it consist of two

parts stretches of 1 cm each?

But why not of a piece ˇof 3 cm,

long and a piece of 1 cm added on in a

negative sense?) | | |

| | | | | | To the philosophical

question, :

“Is the visual image of this tree complex, and what are

its components?”, the right answer

is, :

“That depends

what you understand by

[“|‘]complex’”.

(And this, of course, is not answering the question, but rejecting

it.) | | |

| | | | | | Let us apply the method of

(3) to the account in the Theaetetus:

[L|l]et

us consider a language game for which this ˇis the correct

account. really

holds.

Let [T|t]he language then

serves to describe

combinations of

34 of coloured

on a

surface.

The are squares

and a complex like a

chess board.

There are red, green, white and black squares.

The words of the language are (correspondingly):

“r”, “g”,

“w”, “b”, and a sentence is

a of these

words.

They describe an arrangement of coloured squares in the order

etc..

The sentence “

r r b g g g r w w”

describes then, for instance, an arrangement of this sort:

Here the sentence is a complex of names, to which a complex of

elements corresponds.

The primary elements are the coloured squares:

– “but are these simple?”

–

I can't think of anything

don't know [t|w]hat it

I [w|c]ould be more

naturally to call ˇthe

“ˇ◇◇◇simpleˇ

elements”, in this language

game.

In other circumstance circumstances, however, I

[sh|w]ould

call a coloured square “complex[2|”],

– composed, say, of two rectangles, or of the elements

colour and shape.

But the concept of

‘complexity’ might

also be extended that the smaller surface is said to be

“composed” of a larger surface and one subtracted from

it.

Compare

[“|‘]composition[”|’]

of f[r|o]rces, the

[“|‘]division[”|’]

of a line by a point outside it; these expressions show that

certain circumstances we

are inclined to the

smaller thing as

re[l|s]ult of

the

[“|‘]composition[”|’]

of combining what is

largerˇ things, and the larger

thing as the result of

division of what

is a smaller[.|t]hing

But I don't know whether I should say that the figure which

our sentence describes consists of four elements or

o[r|f] nine.

Well, does

35 does that sentence consist of four

letters of o[r|f] nine? –

And what are its elements: the letter types or the

letters?

And isn't it all the same

quite

indifferent |

which we say, if only we avoid

misunderstandings? in the particular

case?? | | |

| | | | | | But what d[e|o]es it mean, that we can't explain

(i.e. describe) these elements but only name

them?

Th[at|is]

m[g|i]ght mean, say, that the description of a

complex, if this complex

consist[e|s]d[,| (]in a limiting case[,|)] of only

one element square, is simply the name of

the coloured square. // This might

mean, say, that when a complex consists, in a limiting case, of only one

square, then its description is simply the name of

coloured square.

might say

here – although this easily leads to all sorts of

philosophical supers[i|t]itions – that a sign

[|“]r”, or

“[s|b] b”

etc., may sometimes be a word and sometimes a

sentence.

But whether it [“| ‘]is a word or a

sentence[”| ’] depends on the

situation in which it is uttered or written.

If ˇe.g. A has to describe for

B complexes [f|o]f coloure[s|d] squares and

if he uses here the word “r”

,

then we may say that the word is here a description – a

sentence.

But if ˇe.g. he ˇis

memoris[es|ing], say, the words and their what

they meanings, or if he is teaching

the use of

the words and utters them in connection with ostensive

teaching while giving with the

appropriate gesture, then we shall not say that

they are sentences here.

In this situation the word “r”, for instance, is not

a description; you are

nam[e|ing] an element◇ with

it, : – but

it ˇthat's why it would be

st[a|r]ange to say on that account

here th[t|a]t the element can only be

named.

Naming and describing, in fact, are not on the same

level: naming is a preparation for describing.

When you have With In

[[n|N]|n]am[ed|ing]

something youch we

haven'

n[o|']t haven't

yet made a move in the language game, – an[d|y] more than

you' have made a move in

36 in a chess

game by

setting a putting a pieceˇ on the

board.

We may say: with the naming by

giving

of a thing ˇa name

nothingch

ha' yet been done.

It hasn't even yet a name,

– except in the game.

Th[at|is]

is also what Frege meant

by saying that a word has meaning only in the context of

its connection

with |

a sentence.

| | |

| | | | | | What is meant by saying of the elements that we can

ascribe neither being nor not-being to

them? –

might say

something like this: If everything that we call being or

not-being consists in the fact that connections

holding or do or not

holding between the

elements, then there is no sense in speaking of the being

(not-being) o[r|f] an element; just as, if

everything that we call “destroying” consists in

the separating tearing apart

of elemtns elements

ap, it has no sense to speak of destroying an

element.

But we our we

should should like

wish to say:

can't ascribe

atribute predicate being to

of an element, because if it

,

then you it couldn't even

name it be named, and

so you could say therefore [t|n]othing

ˇcould be said of about it. –

dLet' us consider an analogous

case, though, which will make

th[e|is]

clearer[:| .] There is one thing of

which you can't say either that it is 1 m long

or that it isch not 1 m long, and that is the

standard meter in Paris. –

But ˇ, of course, we have

n[o|']t thereby ascribed by

saying this we haven't attributed any peculiar

ˇany curious property to the standard meter, of

course, but have only indicated its peculiar role in the

game process // procedures //

of measuring with the meter-rule. –

dLet' us

samples of